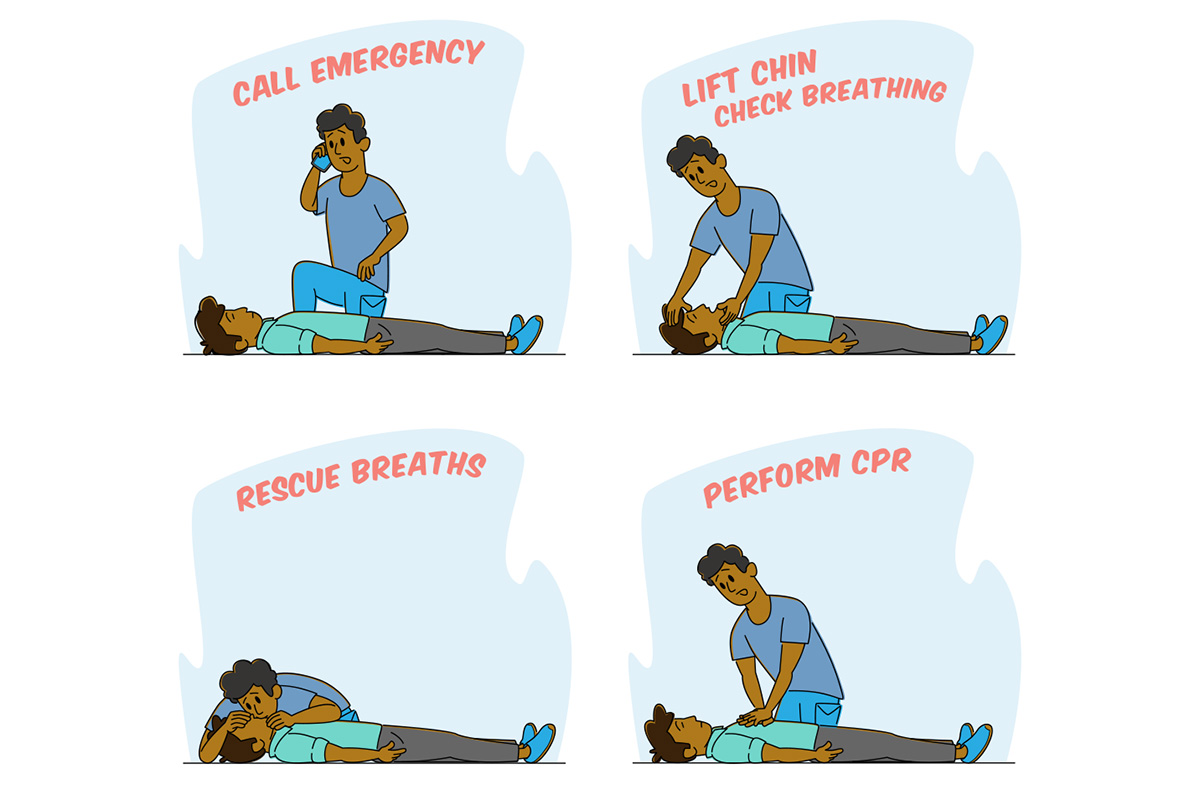

Save a Life with CPR

Following a review of six years’ worth of national data collected by Emory University School of Medicine’s Cardiac Arrest Registry for Enhanced Survival (CARES), a diverse team of researchers found that Black and Hispanic people were significantly less likely than White people to receive potentially lifesaving bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) during cardiac arrest. The study published October 27 in the New England Journal of Medi- cine (NEJM).

The comprehensive analysis showed that Black and Hispanic individuals had 26% lower odds of receiving bystander CPR at home when compared with White individuals.

Those odds dropped significantly in instances of public cardiac arrest, where Black and Hispanic individuals had 37% lower odds of bystander CPR than White individuals going through the exact same emergency event.

Researchers discovered that the disparity between response for Black and Hispanic individuals versus White individuals remained consistent regardless of neighborhood income level or racial and ethnic makeup and regardless of the type of public setting.

Bystander CPR can double or triple survival rates for those experiencing cardiac arrest. The earlier CPR is administered (ideally in the first two minutes after a patient col- lapses), the better the outcome will be.

“As an emergency medicine physician, I know how incredibly important bystander CPR is for cardiac arrest patients,” says Bryan McNally, Emory professor of emergency medicine and executive director of CARES. “Our research team hopes this study will be a catalyst for change to help reduce racial and ethnic differences in cardiac resuscitation and improve outcomes for all communities.” McNally is co-author on the NEJM publication.

Founded by Emory and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2004, CARES serves as a multicenter registry of people who have had nontraumatic, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the US. The registry is fund- ed by the American Red Cross, the American Heart Association, and through state-based subscription fees.

Email the Editor