Can Extreme Sports Make You a Better Scientist?

As a biochemist, Eric Sundberg has always loved structures, especially the three-dimensional structures of protein molecules. “The first time I saw a molecule spin in three dimensions on a computer screen, I was just taken with that,” he says. “What would I do if I were this molecule?”

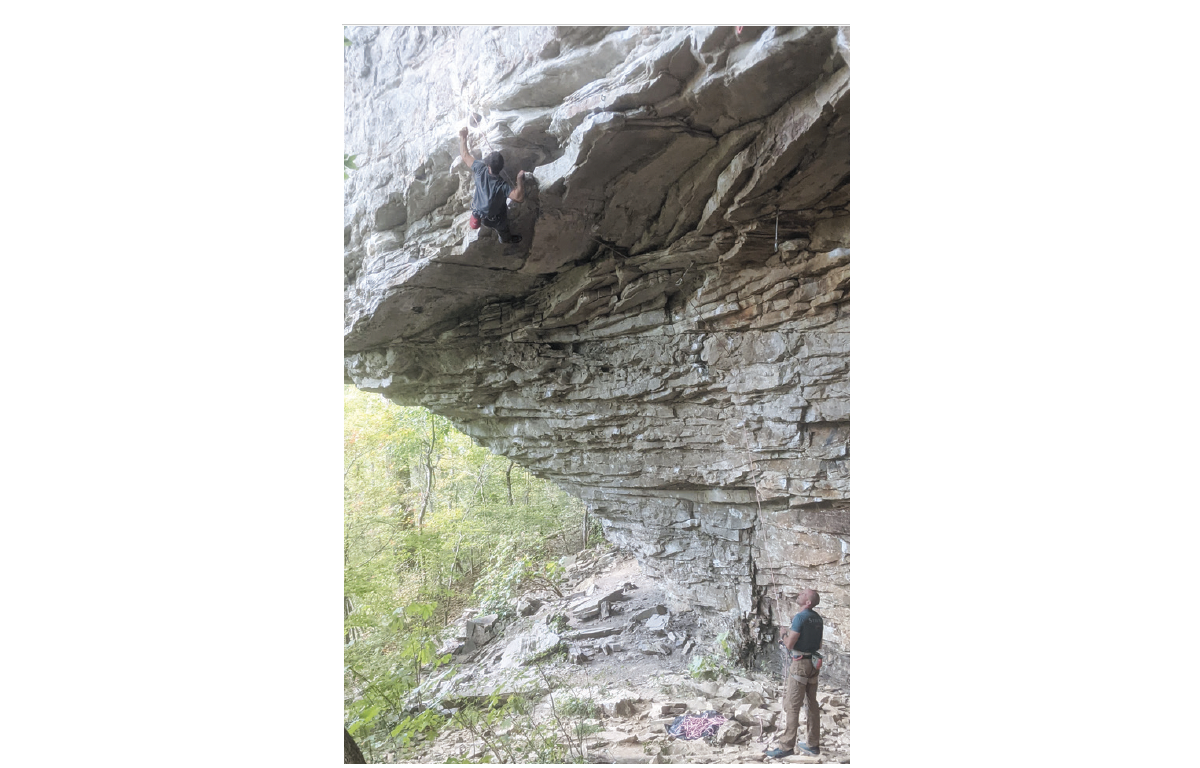

Given that level of interest in granular details, it isn’t surprising that Sundberg, chair of biochemistry in Emory’s School of Medicine, is also a dedicated rock climber who’s explored a range of cracks, crags and rock faces around the world. “There’s obvious parallels,” he says. “How you assess a structure and how you view a protein. If you were to interact with that protein, what kind of strategy would you have for engaging it? Just like if you look up and there’s a giant crack, what’s my strategy for getting up?”

Working hard and playing hard is a way of life for many Emory researchers. Extreme sports provide an almost mystical connection between the two. “Rock climbing has been the one sport I just can’t quit,” says David Reiter, assistant professor of radiology and imaging sciences, even though he played soccer in college. “I’ve gone off and done other things that are more endurance-sport related, but I always end up coming back to rock climbing. It’s got so many dimensions between the physical and the intellectual and the emotional. For me, it’s a big distraction from the things that create stress in my life.”

Sundberg finds the challenges of climbing less a distraction than a lesson in the appropriate mental state to approach research. “That mental toughness and calmness is helpful in our lives as scientists,” he says. “It’s especially helpful when you’re way past your gear, but also in the way you approach the ups and downs and the progress of your career.”

Kenneth Carter has studied that pattern. The Charles Howard Candler Professor of Psychology at Oxford College of Emory, Carter follows extreme risk seekers and even wrote a book about them: Buzz: Inside the Minds of Thrill-Seekers, Daredevils, and Adrenaline Junkies.

“It’s easy to think the high-sensation seekers are outgoing extroverts, but that’s not necessarily the case,” Carter says. “Risk is really the price of admission to the kinds of activities or experiences they want to be able to have. It helps connect them with themselves. A lot of the research suggests the emotional regulation they experience from those endeavors is fulfilling as well.”

Mountain biker Hannah Cebull found her rides to be a rewarding break from the pressures of long hours in the lab. A postdoctoral biomedical engineer in the School of Medicine, she loves riding through natural areas during the changing seasons as well as the challenge of keeping her balance on a narrow trail. “If I’m encountering a tough problem and I get really tired,” she says, “I can’t push my body the same way that I can with biking. So having the physical challenge is a nice contrast to the mental challenge that research brings.”

Marly van Assen agrees. “Research is already super competitive,” says van Assen, co-director of Emory’s Translational Laboratory for Cardiothoracic Imaging and Artificial Intelligence and a long-distance runner. “I’m competitive by nature, and this helps me deal with that because I am not the fastest, not the best runner, but you put in effort and you learn to enjoy it without the need to come in first.”

Last summer, van Assen joined a team of 12 Atlantans competing in an annual relay race from near the peak of Oregon’s Mt. Hood to the beach along the Pacific coast, a total of 197 miles. “I’m from the Netherlands,” van Assen says. “The Netherlands is as flat as you can get. So for me, mountains are super challenging to run, but also really pretty.”

Van Assen climbed Mt. Hood the day before the race. “People were like, ‘You’re gonna run tomorrow,’ ” she says. “‘Do you want to climb up this mountain to touch snow?’ And I was like, ‘Yes!’ So I dragged a few people along and we climbed up, touched snow, then went back.”

Competitors in the Hood-to-Coast race travel in vans when they’re not running. “You don’t really sleep,” van Assen says. “You just do three runs spread out. I had two runs at night. One was at 3 a.m. to downtown Portland. One was at 5 or 6 in the morning through a nature reserve. It is definitely an experience. The finish line is on the beach, and I jumped in the ocean.”

“If I’m encountering a tough problem and I get really tired, I can’t push my body the same way that I can with biking. So having the physical challenge is a nice contrast to the mental challenge that research brings.”

That camaraderie is part of the pattern Carter observes. “When you look at it in a broader sense,” he says, “it’s that connection with ourselves, the connection with other people, the sort of unusual experiences that we’re all after.”

Sundberg’s most memorable moment happened when he took a break from a scientific conference in Rio de Janeiro and met a friend to climb a mountain near Rio’s famous beaches.

“We get up there,” Sundberg says. “And the protection was kind of dodgy, but it wasn’t super hard climbing. The sun’s going down, the lights of the city are coming up and reflecting on the lagoon, and you can see a sight line to Ipanema, a sight line to Copacabana. We stayed up there, I don’t know, half an hour because we’re going to rappel down in the dark anyways. If you’re not a rock climber, you don’t do that. So the combination of the two has been really spectacular."

Email the Editor