Searching for Sickle Cell Solutions

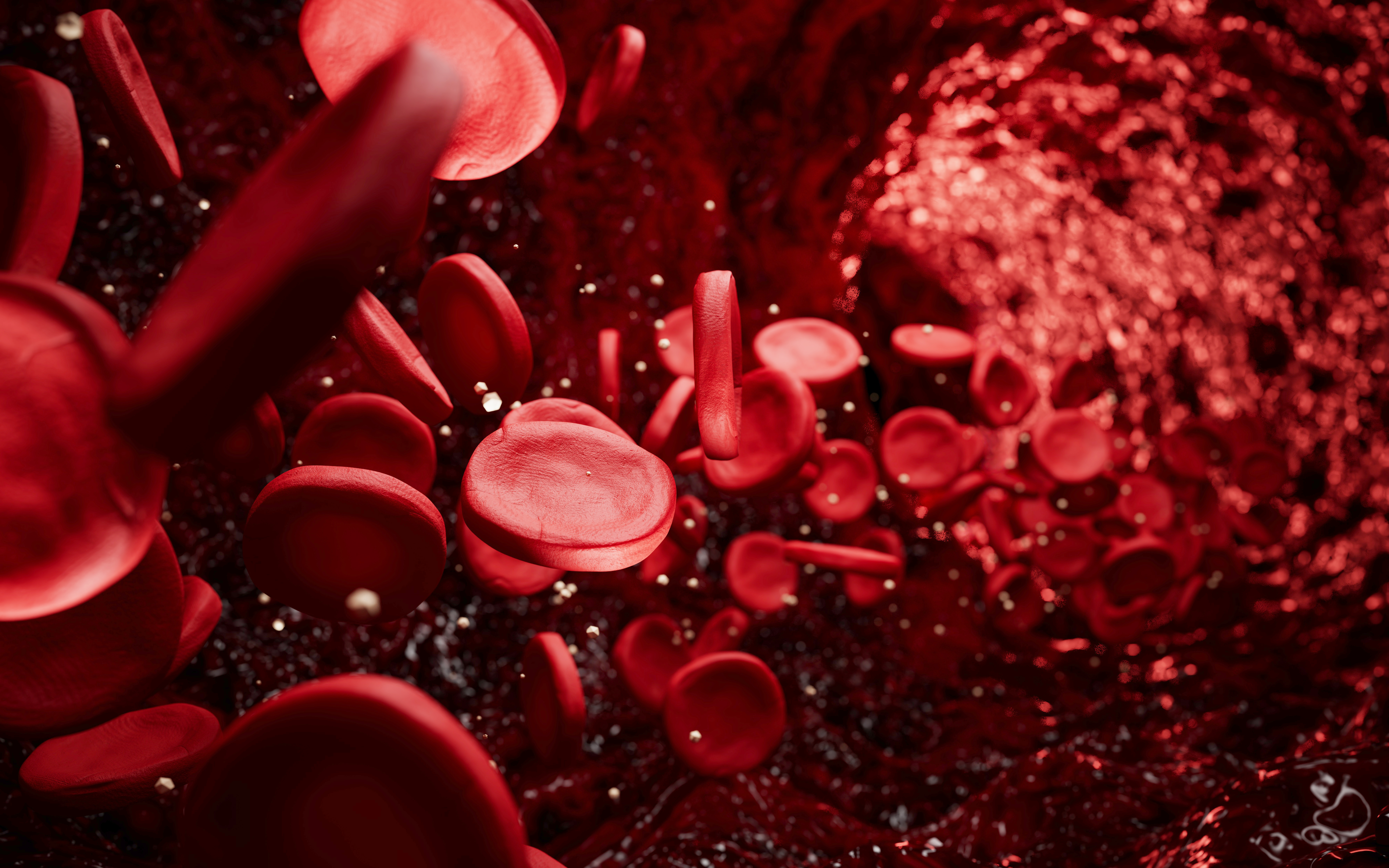

Sickle cell disease, which impacts about 100,000 people in the United States, is a rare, genetic blood disorder in which the red blood cells become rigid and crescent-shaped. It can cause complications including severe, painful episodes of blood-vessel blockages, anemia, fatigue, organ damage, stroke and even a shortened lifespan. It is sometimes known as “sickle cell anemia,” which is a specific type of sickle cell disease.

Photo by Damon Meharg, Emory University

Born in Beirut, El Rassi grew up in Lebanon in the 1980s, in a close-knit family with members carrying the thalassemia gene. “They were difficult times for the country but that did not deter me from pursuing my deep desire to become a hematologist. I went to school at the American University of Beirut, then to medical school there as well. Graduates from the medical school continue their training in the US. You come here for training, with the hope that you will go back home one day and help your community.”

“I still have that hope,” says El Rassi, but for now, his career has taken a different path. “When I came to the US, I did my residency and was at Emory for my fellowship in hematology and medical oncology. I stayed on as faculty. I've always known I had an interest and a deep desire to be a hematologist.

“Lebanon has significant populations of thalassemia and sickle cell disease. I was involved in research on beta thalassemia intermedia and helped show that this population has too much iron in the body. When I came to Atlanta, I found that there's a huge population of sickle cell disease, and it fit into my training and interest.”

Symptom management has been the focus of sickle-cell disease treatment. “But we have had discoveries of therapeutic and targeted agents that have made a difference in the lives of our patients,” El Rassi says. “We hope one day, with better, tailored treatments such as gene therapy, we can have a cure for this disease.”

Sickle cell remains challenging, however. “Gene mapping in general helps, but we know what the gene mutation is in sickle cell. It's one gene that you inherit from each parent, and you end up with the disease.” Carriers of the disease may not experience symptoms, but they can pass it on to their children.

More than 90 percent of adults in the US with sickle cell disease are Black or African American. In the past, factors such as a lack of awareness and systemic racism have led to a lack of resources to study and combat the disease.

But now, says El Rassi, there's the motivation and will to develop new therapeutics and work on cures, with National Institute of Health grants, pharmaceutical company interest, and philanthropic funding. “This is helping to change the field,” he says. “And still, it needs a lot more. This is just the beginning.”

Gene therapy remains promising but is not yet a viable option for most patients, El Rassi says. “We will get there, hopefully in the next 10 to 20 years. In the meantime, we need drug discovery. We need newer and better therapies, medications and agents, to help our patients,” he says. “That’s what I enjoy developing here at our center.”

The first cell-based gene therapies for the treatment of sickle cell disease were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December of 2023. One of the treatments involves the novel gene-editing technology CRISPR.

“The first CRISPR gene-editing technique was approved to treat patients with sickle cell disease,” says El Rassi. “But it's still very early. And the key concern is, what are the long-term safety outcomes of doing such a technique?” Ongoing research is being conducted, he says.

A Debilitating Disease

Sickle cell disease is debilitating due to how it manifests in the body.

“Hemoglobin is what we use to carry oxygen and deliver it to our tissues,” El Rassi says. “Oxygen is the fuel we need. In patients with sickle-cell disease, once the oxygen molecule is given to the tissues, the hemoglobin molecule changes form and becomes sickle-shaped. Hence the name, sickle cell.”

Photo by Just_Super, Getty images

“Sickle cell is a genetic disease that you're born with and live all your life with,” says El Rassi. While it can be detected in newborn screenings, pediatric patients are usually diagnosed between six- to nine-months of age when the first sickling of cells and symptoms appear.

Emory and Children's Healthcare of Atlanta (CHOA) provide comprehensive sickle cell disease treatment for adults and children, including specialized clinics, pain management, and transfusion therapy. The Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center at Arthur M. Blank Hospital is home to the largest pediatric sickle cell disease program in the US. Pediatric care is supported by CHOA's large blood and marrow transplant program. For adults, the Georgia Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center at Grady Hospital offers primary care and 24/7 emergency care. Both institutions provide services like hydroxyurea medication, Transcranial Doppler (TCD) screening for stroke risk and clinical trials.

Children are seen at a dedicated pediatric hematology clinic, then as young adults, transition to the Grady clinic. “So, my relationship builds with patients from the age of 18 and beyond, and we continue to take care of them throughout their life,” El Rassi says. “We use agents that can help reduce complications, but complications still do occur, whether pain events or organ damage that builds up over the years.”

The job of hematologists like El Rassi is to try to reduce such incidents. “Blood transfusions are used in acute cases where there are serious complications. Unfortunately, the blood donor pool is not endless, so we must judiciously choose who to give transfusions to. Transfusions are a mode of therapy, but they're reserved for specific scenarios and situations.”

For example, one of the most severe complications of sickle cell is acute stroke, says El Rassi. To reduce the risk or recurrence of a stroke event, patients need chronic blood transfusions. “And so it is really tailored to each patient, they must have fully matched blood from a marker antigen perspective,” he says. “This is why we're looking to develop even more such therapies, with the help of research, so we can help our patients live longer.”

The current medication most used in sickle cell disease is hydroxyurea, an oral medication approved in the late 1990s that increases the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) and reduces the frequency of painful crises, acute chest syndrome, and the need for blood transfusions. Its alternative use is as a chemotherapeutic agent in much higher doses to control blood counts in Leukemia. Despite its label as chemotherapy, the use of hydroxyurea in sickle cell disease does not lead to the typical chemotherapy complication profile since it is used at a fraction of the chemotherapy dose and monitored by the treating team.

“I can give you examples of patients I have that have lived into their 60s, 70s while taking this medication,” he says. But some patients prefer not to take the medication, and there have been few new therapies for sickle cell that have panned out.

More Treatments in the Pipeline

Research often starts with a deep understanding of patients’ needs.

“I'm a clinician, but I'm also a researcher,” says El Rassi. “And the best way to understand what is needed is by being able to sit with a patient, talk to them, hear their frustrations, and try to find out how you can help them. And that's what we do at the sickle cell center at Grady.”

Research is not something that happens overnight, he says. “At our center, we have been able to start clinical trials and drug development at our site; we now have more and more things in the pipeline. Gene therapy may be an answer, but it's a future answer. We need new and better medications now. And that's what research is helping us with.”

A case in point: “One of my patients had a significant number of pain events. But as new medications and research came around, I was able to enroll her in different clinical trials. And the last clinical trial that she got on, she had a significant response with better control of her sickle cell disease. She was recently able to have a trip to Africa, and that was a dream of hers.”

“So hopefully in the next few years, we can say we've added more to the arsenal, that we can have more agents, keeping our patients healthier longer, so that they can have a good life.”

Email the Editor