A Cure for HIV?

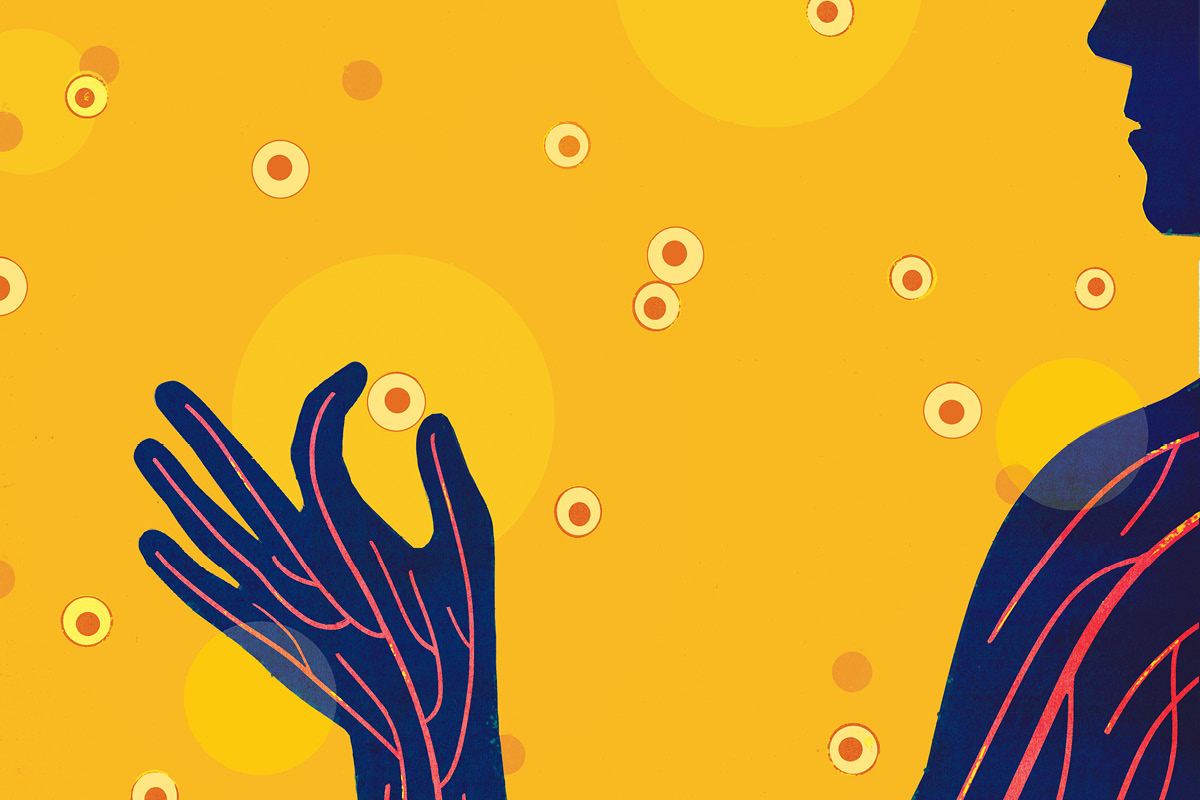

Emory’s pioneering work with a class of small molecules known as JAK (janus kinase) inhibitors continues to show how HIV might be cured, after a second patient who received the treatment was declared to be in longterm remission.

Christina Gavegnano, associate professor in Emory School of Medicine and Emory College

The announcement involved an individual known as the “Oslo patient.” The patient received ruxolitinib, a first-generation JAK inhibitor, for complications following a stem cell transplant from a sibling to treat cancer. Ruxolitinib works as an immunomodulatory drug that may also reduce viral reservoirs. Its potential against the HIV reservoir was first documented by Gavegnano in 2012 and later established in a study led by Emory infectious disease professor Vincent Marconi, with Gavegnano as co-investigator.

The first case of ruxolitinib as part of a potentially curative regimen was documented in the “Geneva patient,” who was declared to be in remission from HIV in 2023 following treatment that included the drug.

Vincent Marconi, professor of medicine and global health at Emory

Gavegnano first came up with the idea to use JAK inhibitors against HIV while working on her pharmacology PhD studies at Emory. Her approach was to reconfigure JAK inhibitors, which were FDA-approved for inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, to control inflammation from HIV by blocking key pathways that allow the virus to persist.

Now she’s preparing to co-lead a new clinical trial using baricitinib, a second-generation JAK inhibitor, to further test the potential for sustained HIV remission without requiring lifelong antiretroviral therapy or a stem cell transplant.

“Courageous efforts from the Geneva patient and his team, and now the Oslo patient and his team, are paving the way for future collaborations and potential for a globally accessible cure for HIV,” Gavegnano says. The first clinical trial using baricitinib for HIV cure research will be co-led by Gavegnano, Marconi, and Andrew H. Miller, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

Email the Editor