All Together Now

Statistics show that injuries are the leading cause of death between the ages of 1 and 44.

The Injury Prevention Research Center at Emory (IPRCE) works to lessen the devasting impact of injury in Georgia and the Southeast through research, education, and outreach. IPRCE focuses its efforts on addressing five leading causes of death and disability due to injury: motorized vehicle crashes, drug overdose, traumatic brain injury, falls, and violence.

In research labs and hospital settings, large numbers of Emory scientists and physicians are engaged in injury prevention research. IPRCE serves as a conduit for them, fostering collaborations that otherwise might not exist, says IPRCE’s director, Jonathan Rupp. More than 80 faculty from Emory and eight other universities, along with 380 community members including state and local public health officials, work with the center.

“This is something that contributes to Emory’s academic mission. It’s something where we are engaging with the community, and we are addressing a major societal problem,” says Rupp. “And combined, that merits the investment.”

Emory physicians treat many of the injuries IPRCE studies, says Sharon Nieb, IPRCE program director. “We have trauma injuries; we have falls,” she says, adding, “Falls are a huge problem in every emergency room. We have falls in our youngest population and in our oldest. Children from zero to four have a higher rate of emergency room visits than even 75-year-olds when it comes to falling.”

In 2020, 1,309 Georgians died due to opioid overdose, and another 1,600 people died on the state’s roads. “The only way we are going to figure out accurately what are the causes and how we address these is with research,” says Nieb.

David Wright is an IPRCE steering committee member and chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Grady Hospital, one of the busiest trauma centers in the US. Most people believe injuries won’t happen to them, he says. “We are all at incredible risk for all types of injury. This is an area people need to pay attention to. The broader community needs to look for solutions.”

The pandemic exacerbated the potential for many of the types of injury IPRCE addresses. Empty roads early in the crisis encouraged speeding and reckless driving that hasn’t abated. Isolation and job losses helped drive up rates of opioid misuse and overdose. Shelter-in-place orders made domestic violence victims more vulnerable. Older adults faced increased risk of falls. And many who injured themselves were reluctant to seek hospital care due to fears of contracting COVID-19.

During the pandemic, IPRCE worked with its agency partners on programs such as the virtual Falls-Free Fridays. Organizers demonstrated exercises for seniors and other ways of keeping themselves safe and preventing falls. “We also had a psychologist talk about the fear of falling, how that often increases people’s risk, and how they can overcome the fear of falling,” says Nieb.

“Our traumatic brain injury task force identified higher rates of head trauma in intimate partner violence patients than other populations,” says Rupp. “So they started implementing screening and referral to services for traumatic brain injury—in particular mild traumatic brain injury, or concussion—at domestic violence shelters.”

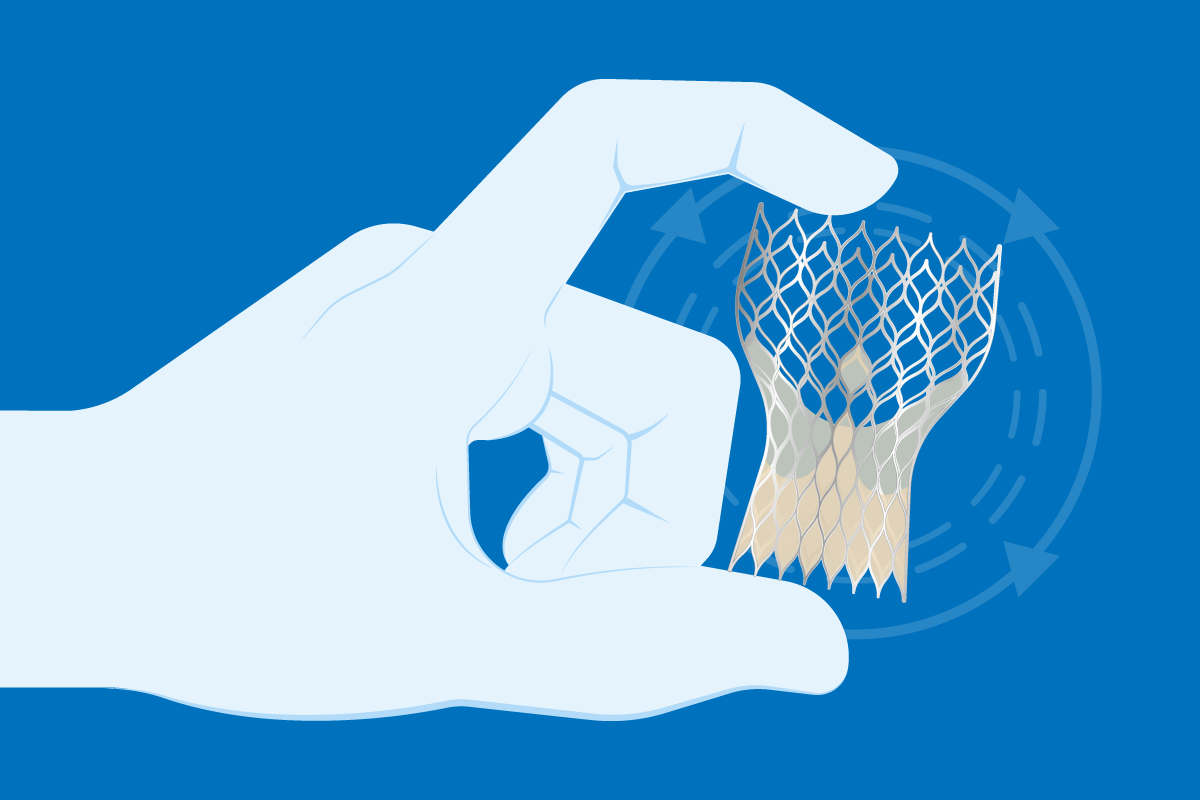

At Grady Hospital, IPRCE member Mara Schenker, Emory professor of orthopaedic surgery, and her team are studying how life-care specialists can help patients after orthopedic trauma and surgery to manage their pain appropriately using opiate and non-opiate medications to make sure these patients don’t progress from opioid use to opioid use disorder.

IPRCE’s Drug Safety task force helped Georgia develop a strategic plan for its opioid response, and the center also advocated for passage of the state’s distracted driving law. IPRCE presented its research to the Georgia legislature as members were debating the merits of the law. It’s doing the same type of research on e-scooter injuries in Atlanta to find out whether the city’s nighttime ban on riding has had a positive impact on injury prevention.

IPRCE executive committee member and Emory School of Medicine Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer Sheryl Heron has studied and treated the impact of violence for more than 25 years as an emergency department physician. “Teen dating violence, gun violence—these are all the unfortunate realities of violence we are trying to address through scholarship, education, and research partnerships.”

Heron worked with Randi Smith, Grady Hospital trauma surgeon and new IRPCE executive committee member on a partnership with Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens’ office for the mayor’s inaugural Peace Week ATL. Smith pulled together the Grady Trauma Program, staffed by the Emory and Morehouse schools of medicine, along with IPRCE’s Violence Prevention Task Force to host a live Twitter discussion on the role of hospitals in implementing public health approaches to violence prevention.

“We think of injuries as a ‘throughout the lifespan issue,’” IPRCE Director Rupp says. “There’s a causal relationship between childhood trauma, or what we call adverse childhood experiences, and behavioral outcomes—both in the near term and intermediate term, and then health outcomes in later adulthood.” IPRCE is working on ways to disrupt the cycle of adverse childhood experiences that lead to poor outcomes in terms of risk-taking and antisocial behaviors as well as substance abuse and other unhealthy lifestyle choices. That’s because, in terms of injury prevention, the familiar adage proves true. An ounce of prevention really is worth a pound of cure.

Email the Editor