Extraordinary Care

Families have a place to turn for help with sex chromosome disorders

Photo by: Jack Kearse

Emma St. Germain, a dark-eyed, dark-haired eight-year-old, loves playing with dolls and Legos.

“Families have been falling through the cracks for decades,” says Sharron Close. “Our clinic meets a tremendous need.”

Shy at first, Emma warms up quickly when Sharron Close, the pediatric nurse practitioner at the eXtraordinarY Clinic at Emory, notices the doll she’s holding.

“Tell me about her,” Close says to Emma, who has come for a follow-up on her condition, a sex chromosome disorder called trisomy X. Within minutes, Emma and Close are looking at doll outfits on a smartphone.

During the visit, Emma’s mother talks with Amy

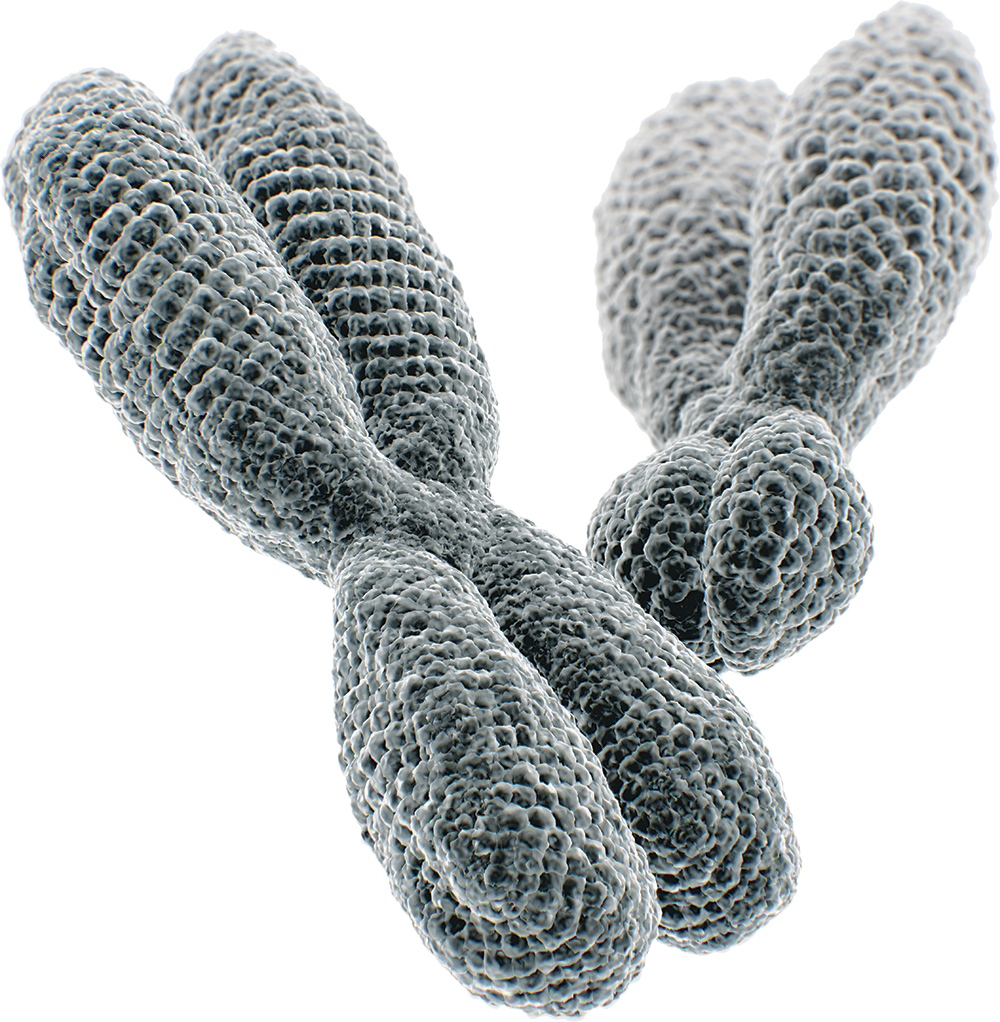

Humans are typically born with 46 chromosomes in 23 pairs. The X and Y chromosomes determine a person’s sex. Most women are 46XX and most men are 46XY. In a few births per thousand, some infants are born with a single sex chromosome (45X or 45Y) and some with three or more sex chromosomes (47XXX, 47XYY or 47XXY, etc.) Additionally, some males are born 46XX due to the translocation of a tiny section of the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome, and some females are born 46XY due to mutations in the Y chromosome.

Source: World Health Organization

Talboy’s assessment is welcome news for Tori, who has pushed Emma’s teachers to provide her with more individualized instruction.

Until recently, families like the St.

These variations are not inherited and occur randomly when girls (XX) and boys (XY) are born with more or fewer than the expected number of sex chromosomes. Some people born with trisomy X (occurring in one out of 1,000 female births) and XXY or Klinefelter syndrome (occurring in one out of 500 male births

“Families have been falling through the cracks for decades,” says Close. “Our clinic meets a tremendous need.”

Close and Talboy currently see patients, mostly from the Southeast, who have been diagnosed via chromosome analysis. The clinic evaluates their needs and connects children and parents with early intervention programs, speech and language therapies, and occupational and physical therapies as needed.

As their patients grow older, clinicians can address problems related to sexual development during puberty.

The clinic also counsels expectant parents about

“The first time we met, we had five or six times more people than we expected,” says Amy Talboy. “Everybody feels they are on their own, and when they come together, it’s just remarkable.”

A genetic counselor, nurse navigator, neuropsychologist, pediatric endocrinologist, and adult urologist staff the clinic, in addition to Close and Talboy. The clinic sees patients once a month and has a waiting list. Its co-directors are considering adding a second clinic day.

“We are growing a step at a time,” says

With the help of the eXtraordinarY Clinic, Emma has successfully completed physical therapy, occupational therapy, and vision therapy. Learning remains a challenge, as do the seizures and migraines she has experienced since age four.

Hiding in Plain Sight: Sex chromosome disorders occur in one of every 400 live births, but too often remain undiagnosed until much later—if at all. To increase awareness, Emory nursing researcher Sharron Close is collaborating on a documentary with filmmaker Dianne Steinkraus, whose sister, Carole, was diagnosed with trisomy X at 53. The diagnosis finally explained Carole’s lifelong struggles with anxiety, insecurity, and difficulty connecting with friends and family (as well as her reaching the height of six feet by age 12). Now in her early 60s and in assisted living in Minnesota, Carole inspired the documentary, which will feature experts and projects from around the country, including the eXtraordinarY Clinic at Emory. “There probably are many other women like Carole,” says Close. “The truth is, they most likely have escaped being diagnosed during their lifetime. Advances in genetic testing now make diagnosis possible.”

Clinicians believe she may outgrow the seizures. The cause of her migraines remains unknown for now.

“If you put 15 girls with trisomy X in the same room, each one would present with different problems,” says Close, an assistant professor at the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing. “We’re here to support families and figure out a targeted therapy for each child.”

In years past, families affected by X and Y variations had few treatment and research options. To close the gap, Close organized conferences in 2015 and 2016 to engage patients, families, doctors, and researchers in developing ways to help children and parents manage X and Y symptoms and cope with the issues they face.

Georgia Governor Nathan Deal signed a proclamation declaring May as X & Y Chromosome Variation Awareness Month, marking a milestone in a grassroots campaign led by Close, Talboy, and Dorothy Boothe, whose teenaged son has XXY syndrome.

Boothe is a parent leader with the Southeastern Regional X and Y Support Group, which draws patients and families from Georgia and five surrounding states. The group meets bimonthly, often at Emory. “The first time we met, we had five or six times more people than we expected,” says

When Tori St. Germain brought her daughter Emma to the eXtraordinarY Clinic, she found solace in being at a place that understands her family’s needs. Her younger daughter, four-year-old Megan, has a different disorder—chromosome 6, a rare type of genetic disorder that can cause speech and developmental delays and chronic health conditions.

A devoted mom, Tori has learned everything she can about her daughters’ conditions to help them grow up normally. Each day has its joys and challenges. “It’s a lot to deal with,” she says. “The eXtraordinarY Clinic is there to listen and to help.”

TO SUPPORT clinical care and research for patients with sex chromosome variations, contact Amy Dorrill, senior director of development, at 404.727.6264 or amy.dorrill@emory.edu.

Email the Editor